REINDEER MAN

On View:

August 2021: Bear Gallery in Fairbanks, Alaska

September 2021: Kenai Art Center in Kenai, Alaska

“Reindeer”

Plate: 2″x3″ etching and drypoint on copper

Paper: 5″x6″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 40, $15 ea

I first became aware of Reindeer George in 2015 when my buddy Simon started helping out at Archipelago Farms. It was easy for me to romanticize the simple, dignified way of life that I saw in his photos; while I was stuck in Texas traffic they were hauling buckets of feed through the snow, surrounded by these mythical animals. I stored the idea that the reindeer farm might provide good source material for paintings down the line. In 2019 I found myself back in Alaska, and when the Fairbanks Arts Association agreed to host an exhibition of my work it seemed like the perfect time to finally collaborate with George. He agreed, and we both dove in.

My idea was to present the reindeer lifecycle from birth to slaughter, keeping the real focus on the human trials throughout. I wasn’t sure what kinds of images would emerge, other than people in the quiet rituals of manual labor, like in the paintings of Millet and Breton. I was initially concerned that my pictures might end up too safe, with too little at stake, like so many thrift store farm paintings. Those concerns disappeared on my first fact-finding mission, when I accompanied George to the slaughterhouse. In that small, wet room, full of blood and the smell of rumen, there was a sober dose of reality worth sharing.

After that I ditched all preconceived ideas and let the pictures come naturally from spending time on the farm, lending a hand, and talking to George. I found his world to be one of many small dramas, endless troubleshooting, and people working with—and struggling against— nature. George was a true collaborator. He granted me access to all aspects of the farm, even the grittier, darker corners, and nothing was off limits for depiction. George loves his work wholly and owns it, and so he doesn’t wince at any part of it.

These paintings and etchings aren’t meant to be a biographical account of George’s life, and they are far from being a complete account of all the work done at the farm. These are a few selected scenes that I found particularly poetic, and they attempt to transmit the sense of humanity that I witnessed during my time at Archipelago Farms. I never got any better at farming, and George never got any better at painting, but we hope you enjoy this collaboration, made by two people with sincere devotion to their respective crafts.

-Alex Rydlinski

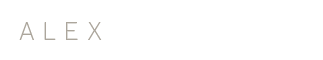

Self Portrait, oil on canvas, 13″x13″ SOLD

Reindeer George

“Reindeer George” oil on canvas, 24″x24″ $2,175

George Aguiar of Archipelago Farms grew up on a large dairy farm in California’s Central Valley, where his father was the herdsman. His family immigrated from the Azores islands and maintained many of their traditions, including many cultural food traditions. From a young age George raised rabbits, pigs, cows, and goats, and realized early on that he wanted to be involved in the animal production world.

This career goal led George to pursue a B.S. in Natural Resource Management at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, which eventually led to his employment by the Reindeer Research Program. Here George acquired his introduction to not only fenced reindeer at the Fairbanks Experiment Station Reindeer Research Program herd, but he also applied these research concepts on the free range herds owned by Native Alaskans on the Seward Peninsula. During his work with the Reindeer Research Program, George acquired his graduate degree, which placed emphasis on reindeer production.

George founded Archipelago Farms in 2009 with the purchase of 6 reindeer from British Columbia. After partnering up with a local farmer to share expenses and pool resources, they made the 1,500 mile journey, and the reindeer found themselves nestled on a small farm in the Goldstream Valley. In 2014 George went back for an additional 6 reindeer to ensure enough genetic diversity for future production goals. Currently he maintains the herd between 30 and 50 head.

As the farm grew, so did the all-too familiar challenges of feed and infrastructure costs associated with production agriculture in a sustainable business model. At one point the dream seemed to be over. Feed was too expensive, and the herd was not large enough to cull animals while maintaining a critical herd population. Then a yearly lease opportunity with the long running Riverboat Discovery suddenly made itself available. It was enough to keep operational costs manageable while exploring other opportunities. Eventually, bookings at events for the halter-trained animals became regular. Local businesses such as HooDoo Brewing Co., Compeau’s, and Toy Quest all began hosting events, and reindeer were requested for functions at schools and military bases. Reindeer have even partaken in weddings, private parties, and concerts. Eventually the herd became big enough to collaborate with local restaurants. 229 Parks Restaurant and Tavern, Hungry Robot, and Lemongrass were three of the first to provide Archipelago Farms’ reindeer on the menu locally in Fairbanks. Alaska Interior Meats and Mid-Town Market have made it possible to distribute product throughout the community as well. Boreal Winds, a soap maker in town, collaborated by utilizing reindeer tallow and milk in some of her soap lines. Eventually, live animal sales both in-state and out-of-state became an expected means of income. These collaborations with other businesses, plus the support shown by the community, has allowed Archipelago Farms to survive and stick around for the foreseeable future.

Most recently, a collaboration between George Aguiar and Alex Rydlinski has allowed for some of the daily farm trials and tribulations to be presented visually via etchings and paintings. Not only did Alex make it his priority to involve himself with the farm and its challenges throughout the year, he also strived to understand the animals’ natural disposition and life cycle to most accurately depict some of the less-talked-about intricacies of this lifestyle, and all of the human struggle and emotion that is often times dismissed.

The Newborn

“The Newborn” oil on canvas, 30″x40″ SOLD

Reindeer calves in Alaska are born in late March/early April, about a month sooner than the Scandinavian calving season. In Fairbanks, that usually means lingering subzero temperatures. The farmer stays nearby to make sure the interaction between the cow and calf are normal, and that the calf nurses right away to get the colostrum so critical to a newborn.

The New Mother

“The New Mother”

Plate: 7″x7″ etching, aquatint, and drypoint on copper

Paper: 11″x11″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, SOLD OUT

A new mother has about a week to get her calf through its most vulnerable stage before she sheds her antlers. Then she’ll have no weapons to protect against more dominant cows, and the established hierarchy of the herd can change. During that week she must bond with the calf, get it mobile, and incorporate it into the herd. Here the calf is seen nursing while the new mother stands guard while she still can.

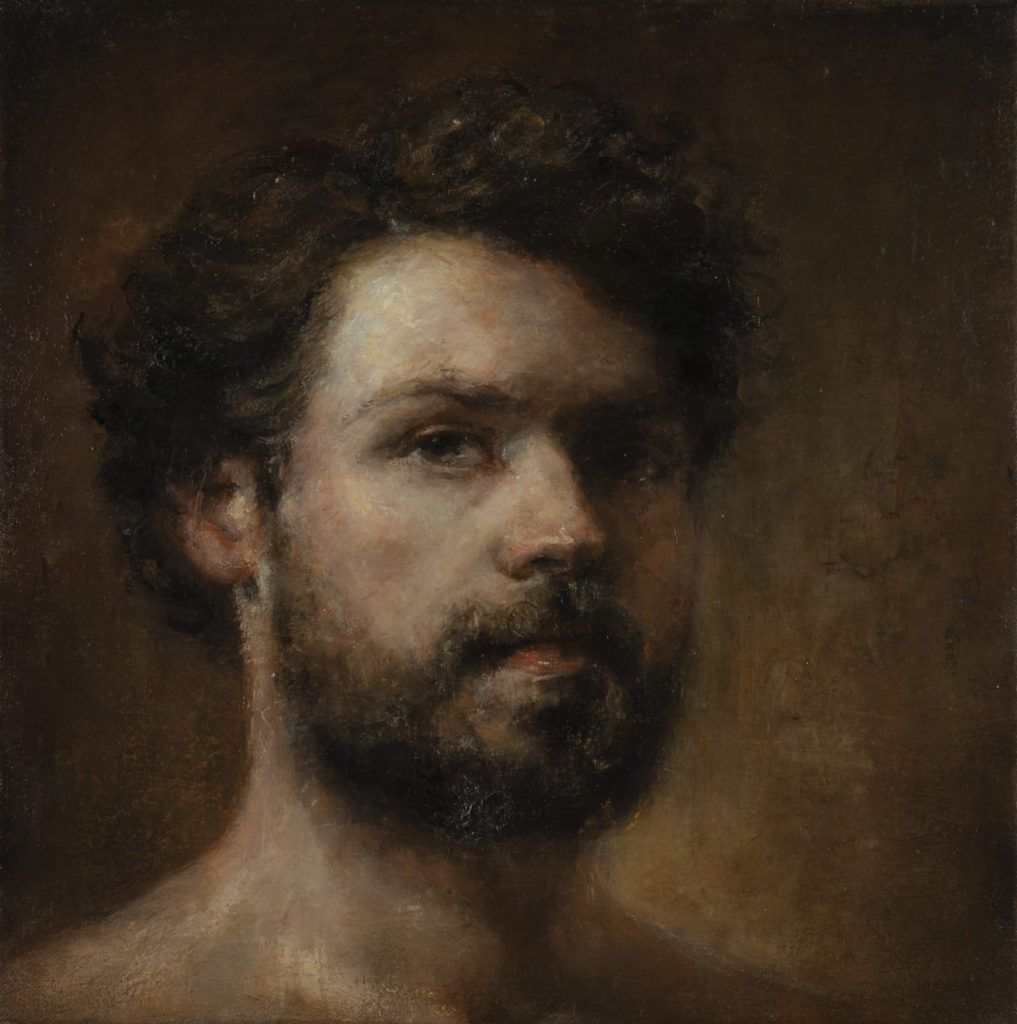

Raven Watch

“Raven Watch”

Plate: 7″x5″ etching, aquatint, and drypoint on copper

Paper: 11″x9″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $40 ea

When the new calves arrive, so do the ravens. If given the opportunity, ravens can swarm on the vulnerable calves, picking out their eyes and tongues, and leaving them for dead. The farmer shoos the protected birds away ceaselessly, and can’t leave the farm unattended for the entire calving season.

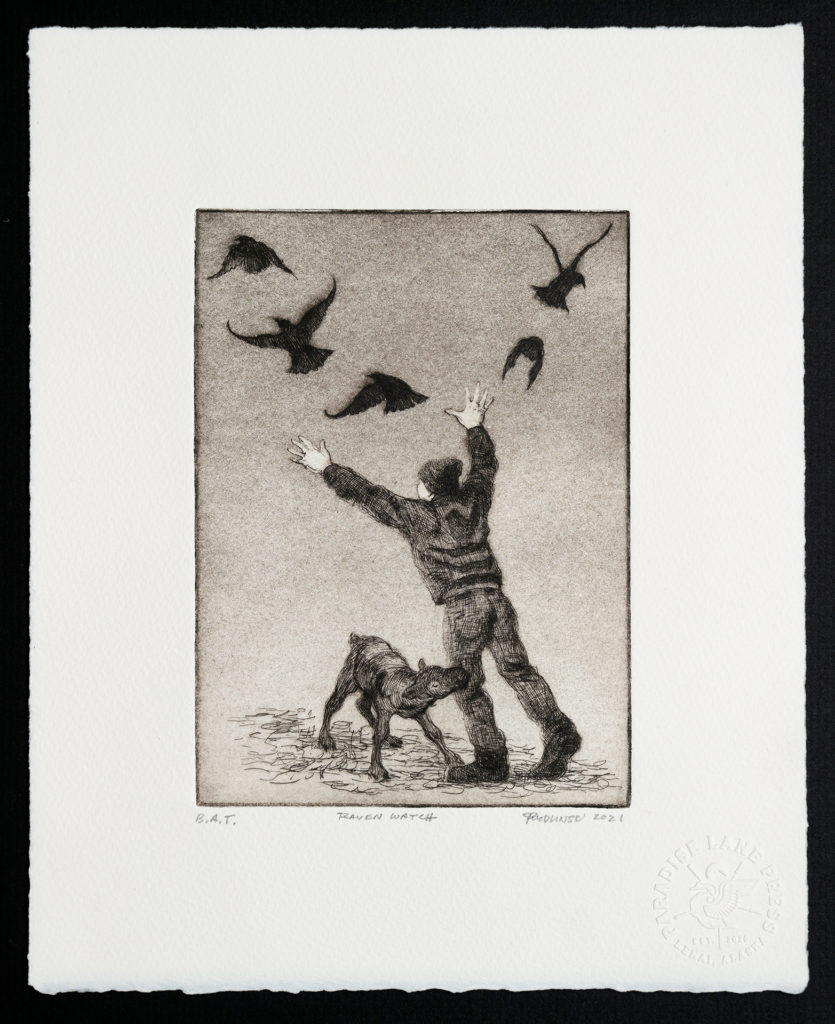

He Could Not Be Saved

“He Could Not Be Saved”

Plate: 6″x7″ etching, aquatint, and drypoint on copper

Paper: 10″x11″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $45 ea

Calf mortality on the farm is lower than in traditional reindeer herding because the animals are so closely monitored. However, this calf was born with a blood clotting disorder, and while the vet was called right away and she made near heroic efforts, the calf’s life was over before it started. The farmer feels the loss, but has to stay focused on the survival of the rest of the calves.

The Bottle-fed Calf

“The Bottle-fed Calf” oil on canvas, 20″x30″ SOLD

When a newborn calf gets sick or the mother refuses to care for it, the farmer may need to bottle-feed the calf. Reindeer that were bottle-fed as calves are typically more comfortable around people, less reactive to triggers, and less stressed being away from the herd, so they’re often easily halter-trained and taken to live events. However, animals that were bottle-fed can sometimes have trouble integrating with the herd, and their abnormal behavior comes with a different set of challenges and risks, especially during breeding season.

The Squeeze Chute

“The Squeeze Chute” oil on canvas, 30″x40″ SOLD

The loss of antler velvet indicates the start of the rutting season, when bulls are at their most vulnerable and aggressive. When a reindeer needs attention (ear tagging, hoof trimming, medicine, etc.) it is guided into a tight, padded enclosure called a Squeeze Chute, securing the animal for safe handling. Normally this is a low-stress procedure, but the rare handling of a rutting bull is one of the most difficult and dangerous tasks on the farm. The bull depicted here developed an infection that required immediate attention. The farmer relies on his friends and volunteers to safely get the bull cleaned up and injected with an antibiotic.

The Rut

“The Rut” oil on canvas, 30″x40″ $3,175

Reindeer are separated into harems weeks in advance, before any animals lose their velvet. This allows them to establish their new hierarchy before the aggression of the rut kicks in. Bulls eat considerably less during the rut, and can lose up to a third of their body weight in 6 weeks. The cows shed their velvet after the bulls, as they individually become ready to breed. Reindeer relations are closely monitored so that everything goes according to plan.

The Winter Bull

“The Winter Bull” oil on canvas, 20″x30″ SOLD

In the fall, during rutting season, the bulls are at the top of the hierarchy. Afterwards, when they shed their antlers, the bulls fall to the bottom, and are at their skinniest and weakest heading into the harsh winter. The cows keep their antlers until after calving, and can make the bulls wait to eat until the rest of the herd has gotten its fill. The farmer looks after the bulls in this vulnerable state, and in some cases even separates the bulls from the herd.

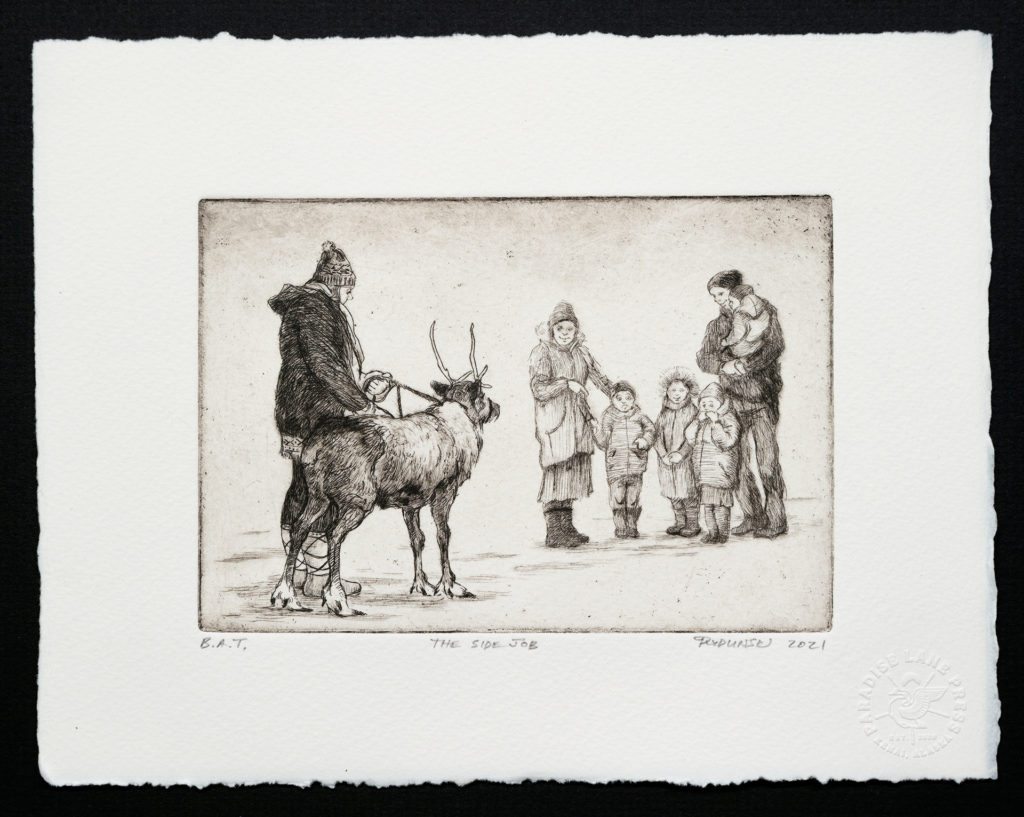

The Side Job

“The Side Job”

Plate: 4″x6″ etching and drypoint on copper

Paper: 7″x9″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $35 ea

Some reindeer, like bottle-fed-calves, are great animals for live events. These reindeer get the chance to go on the road, meet people, and pose for pictures. People love interacting with reindeer, so it’s a win-win for the farm and the community, especially around the holidays.

Dogs!

“Dogs!”

Plate: 9″x12″ etching, aquatint, and drypoint on copper

Paper: 13″x16″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $60 ea

Loose dogs and farmers have been mortal enemies for centuries, and a reindeer farm in sled dog country is no exception. This image is based on a true event when three huskies got into a pen at Archipelago Farms. The dogs terrorized and injured a few reindeer, and one reindeer had to be put down due to its injuries. The dogs were unharmed and restrained, and amends were made.

The Night Errand

“The Night Errand” oil on canvas, 26″x36″ SOLD

Unlike traditional reindeer herding where the animals subsist only on grazing and foraging, farmed reindeer rely solely on their caretakers for food. The farmer devises a specific nutritional program that works best for his animals. The scene depicted here is easily the most fantastical experience on the farm. On trails lit only by a headlamp and the northern lights, the farmer is greeted by reindeer from the shadows as he sets out with buckets of feed. The seasonally blue reindeer eyes catch the light in the darkness.

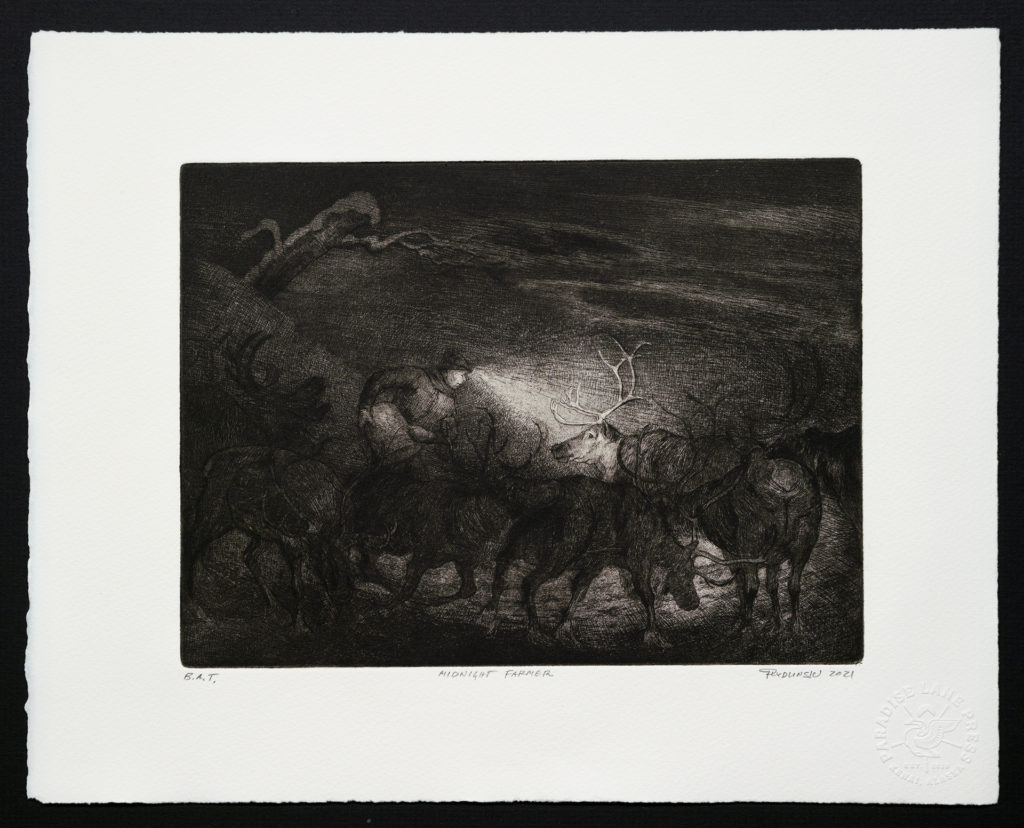

Midnight Farmer

“Midnight Farmer”

Plate: 7.5″x10″ etching, aquatint, and drypoint on copper

Paper: 11.5″x14″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $60 ea

The daily feeding ritual can never be skipped, so if the farmer has a particularly busy day, or wants to grab dinner or a beer with friends, he is often feeding the animals late into the night. George has earned the nickname “Midnight Farmer” because of his frequent late night feeds.

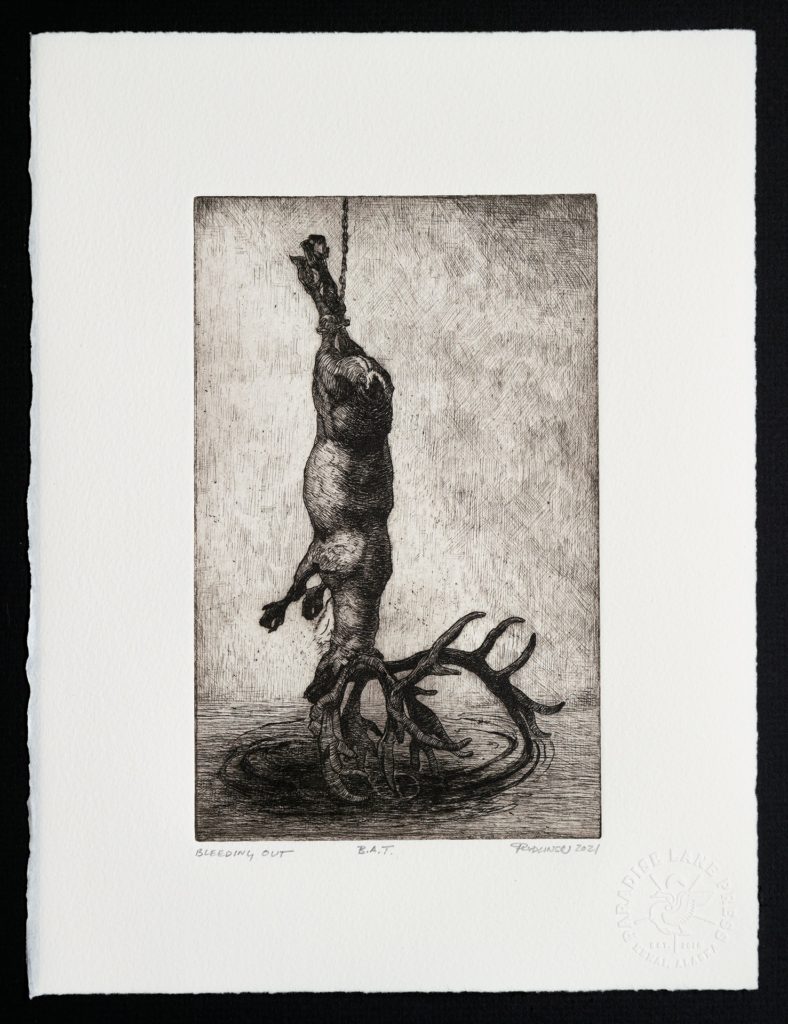

Bleeding Out

“Bleeding Out”

Plate: 8″x5″ etching and drypoint on copper

Paper: 12″x9″ Arches white 250gsm mouldmade deckled edges

Edition of 25, $45 ea

All slaughtered animals must be bled before processing. When too much blood is retained in the meat it becomes more prone to spoilage, and blood acts as a carrier for food borne pathogens. The blood also seems to carry in it the essence of the animal; when the blood is gone, only a carcass remains. After this animal stopped bleeding, I heard the butcher ask the farmer in past-tense, “what was his name?”

The Slaughterhouse

“The Slaughterhouse” oil on canvas, 40″x30″ SOLD

It’s never easy to bring an animal to slaughter, especially one that’s been at the farm for 8-10 years, but meat production is what keeps the farm alive. Seen here is a veteran butcher and his team in the slaughter process while a USDA inspector looks on to ensure food safety. Each part of the animal is valuable and utilized: the antlers, hide, and meat. Each reindeer supplies Alaskan businesses and restaurants with a sustainable local food source.

Anatomy of an Etching

Etchings are made by first coating a copper plate with an acid-resistant ground, then drawing into the ground with a needle, exposing the bare copper. The plate is submerged into a bath of mordant (traditionally acid, but I’m using Ferric Chloride) and the exposed copper is “bitten” away, etching the drawn lines into the plate. The ground is then removed, and the plate is inked and wiped clean, leaving ink only in the recessed, etched lines. A sheet of damp paper is placed on the inked plate and ran through a high-pressure printing press. The paper lifts the ink from the etched lines, producing a print. This process can be repeated many times, creating an edition of prints.

The plate can be developed over many states until the final etching is achieved. I like to pull a print of each different state to use as a reference for the next state. It’s unusual to display these clumsy middle stages, but I think it’s an interesting look into the versatility of this fantastic medium. Excuse the wrinkled paper, only final prints get flattened.

* This part of this exhibit can be seen better in the 3D viewer at the top of the page

States 1-7

Developing the drawing. Even though the picture was going to be very dark, I wanted strong line work in the shadows. Line depth and thickness are controlled by how long the plate sits in the mordant. Longer times mean bolder lines.

States 8-10

Tonal areas are produced in etchings by a technique called aquatint. It’s achieved by coating the plate in a fine mist or dusting of acid-resistant material (traditionally powdered rosin, but I’m spraying liquid stop-out through an airbrush.) The mordant etches the metal around the atomized dots of stop-out, and that surface holds ink to produce a printed tone. The darkness of the aquatint tone is controlled by how long the plate sits in the mordant. I didn’t get the tone nearly dark enough in State 8, setting myself up for a long struggle.

States 11-12

Frustrated with the aquatint, I decided to reground the plate and use etched lines to finish darkening the scene.

States 13-18

Copper is soft and etched lines can be ‘erased’ by rubbing with a burnishing tool until the line is flush with the surrounding copper. Here I’m whitening the glow of the headlamp by burnishing. Drypoint lines are achieved by drawing with an etching needle directly onto the copper. Whereas mordant removes material completely, drypoint lines leave a copper burr which holds ink, creating a softer, feathery line.

State 19

Here I decided the plate was finished, but I didn’t like the way I had wiped it, leaving a little too much ink in some of the drypoint lines. I inked the plate again and printed it, which became the “Bon a Tirer” print (B.A.T.) meaning it’s ready to go ahead with the edition. That print is on display across the room in this exhibit.

Final Plate

Here is the final copper plate. You can see how different the plate seems compared to the mirrored printed image, which is one of the many reasons I find etchings so challenging and rewarding. They are always a little magical when they come out right.

Studies

I made several research trips to George’s farm here in Fairbanks, but all the artwork was actually executed down in Kenai, where I live. These studies helped me come up with the reindeer poses for all the paintings and etchings, and the clay maquette was helpful as a reference for lighting, especially in “The Night Errand.”